Entries in First Amendment (8)

"Dirtiest Hotel" Case Teaches that Brand Owners Shouldn't Sue Over Bad Reviews

I’m giving a talk next week about protecting your brand on social networks.

The theme of my talk is that a trademark owner’s ability to stop others from saying bad things about its brand is limited.

Quite limited.

Just ask Kenneth Seaton, owner of the Grand Resort Hotel and Convention Center. He sued TripAdvisor LLC, who runs the TripAdvisor travel Web site. TripAdvisor named the Grand Resort Hotel to its “2011 Dirtiest Hotels” list. You can guess its commentary wasn’t very favorable.

Mr. Seaton asserted claims for defamation, false-light invasion of privacy, trade libel/injurious falsehood, and tortious interference with prospective business relationships.

The district court threw out the case in short order. It found Mr. Seaton could not prevail on his claim given TripAdvisor’s broad First Amendment protection.

On Aug. 28, the Sixth Circuit affirmed. It found: “Seaton failed to state a plausible claim for defamation because TripAdvisor’s placement of Grand Resort on the ‘2011 Dirtiest Hotels’ list is not capable of being understood as defamatory; it is protected, nonactionable opinion. TripAdvisor’s use of the word ‘dirtiest’ constitutes loose, hyperbolic language, and the general tenor of the ‘2011 Dirtiest Hotels’ list makes clear that placement on the list cannot reasonably be interpreted as stating actual facts about Grand Resort.”

It added that Mr. Seaton’s other claims “appear to attempt to bypass the First Amendment” and, therefore, must similarly fail.

Brand owners should take note. They can take vigorous steps to protect against damage to their brand through confusingly similar trademark use, false advertising, and other forms of unfair competition. However, they should know their rights have limits — and the First Amendment is one of them.

As the Grand Resort Hotel demonstrates, trying to silence critics or erase bad reviews by going to court is a bad idea.

Links to a good write-up and case documents available here via the Digital Media Law Project.

The case cite is Seaton v. TripAdvisor LLC, __ F.3d __, No. 12-6122 (6th Cir. Aug. 28, 2013).

Trademark Law in the Age of Social Media: CLE Coming Soon

When the First Amendment collides with the Lanham Act,

When the First Amendment collides with the Lanham Act,

the First Amendment usually wins. (As is evident from the above parody.)

I’m speaking at an upcoming CLE on social media.

My topic, of course, is trademark law in that context.

My presentation materials are here. I will publish my slides when the presentation is over.

The issues are good, as well as the slate of other speakers. More details available here.

The CLE spans two days: Sept. 6 and 7, at the Washington State Convention Center.

If you attend, please say hello!

If Parody is Exempt from Dilution, Why isn't It Exempt from Infringement?

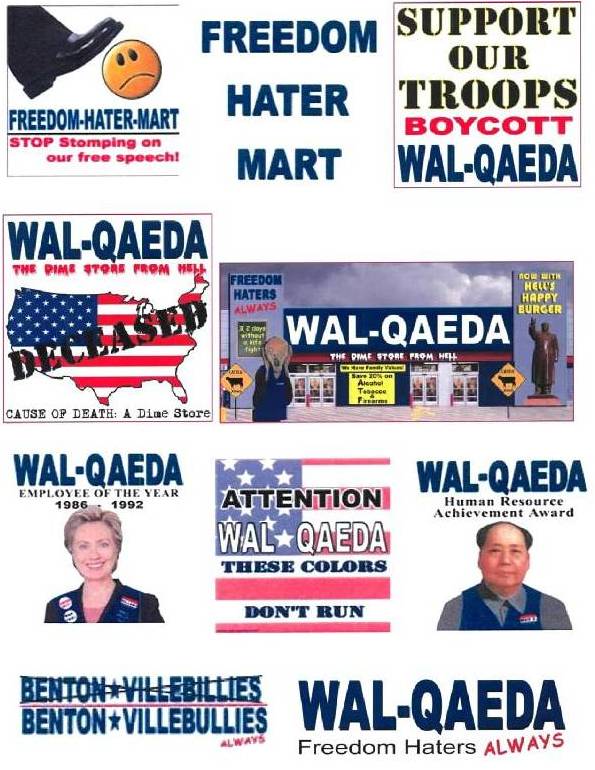

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Discussing parody in my Advanced Trademark Law Seminar.

I’m stumped on one point.

In a number of cases involving the parodic use of a trademark, courts apply likelihood of confusion analysis to infringement claims. Successful parodies do not cause a likelihood of confusion, so they do not infringe trademark rights.

Analyzing dilution claims, however, courts in the same cases often treat parodies as noncommercial speech. For that reason, they conclude parodic uses are exempt from dilution claims.

In Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 537 F.Supp.2d 1302 (N.D. Ga. 2008), for example, the court concluded Charles Smith’s use of WAL-QAEDA was not likely to confuse consumers with Wal-Mart’s trademarks, so Wal-Mart’s infringement claim against him could not stand. With respect to Wal-Mart’s dilution claim, the court found WAL-QAEDA succeeded as a parody because it communicated Mr. Smith’s negative feelings about Wal-Mart. “Thus, Smith’s parodic work is considered noncommercial speech and therefore not subject to Wal-Mart’s trademark dilution claims….” In other words, Mr. Smith’s parody did not trigger the dilution statute because it was noncommercial.

Similarly, in MasterCard Intern. Inc. v. Nader 2000 Primary Committee, Inc., 2004 WL 434404, *9 (S.D.N.Y.), the court found Ralph Nader’s use of MasterCard’s trademarks in a political ad that spoofed MasterCard’s “Priceless” advertising campaign was not likely to confuse consumers, so it dismissed MasterCard’s infringement claim. With regard to its dilution claim, the court concluded the Nader campaign’s use of MasterCard’s mark was “political in nature, not within a commercial context, and is therefore exempted from coverage by the Federal Trademark Dilution Act.” Again, noncommercial use did not trigger the statute (though this time it was because the ad was political, not because it was a parody).

The answer’s probably sitting there in McCarthy on Trademarks, but if a use that’s deemed noncommercial does not trigger the dilution portion of the Lanham Act, why does it trigger the infringement portion of the Lanham Act?

I realize the dilution portion of the statute expressly excepts parodic and noncommercial use — and infringement finds its roots in common law —but if my use of a trademark is deemed to be noncommercial, why do I have to go through likelihood of confusion analysis to determine if such use nonetheless infringes a trademark owner’s rights? Seems like a finding that my use is noncommercial would be the same “Get Out of Jail Free” card for infringement that it is for dilution.

Anyone willing to tell me why it’s not?

Western District Quashes Subpoena Intended to Learn Owner of Gripe Site

Still anonymous: Screen shot from defendant’s Internet gripe site

Still anonymous: Screen shot from defendant’s Internet gripe site

The anonymous John Doe runs the Internet gripe site, www.SaleHooSucks.com, which criticizes plaintiff SaleHoo Groups, Ltd.

SaleHoo is a New Zealand limited liability company that offers a database of wholesalers and brokers of goods that can be sold on eBay, and sells memberships that authorize access to the database.

Mr. Doe’s site claims that SaleHoo threatens individuals who post unfavorable information about SaleHoo with defamation lawsuits and thus “there is no way to get true unbiased reviews of SaleHoo.”

SaleHoo, which owns the trademark SALEHOO, filed suit in the Western District against Mr. Doe for for trademark infringement, among other claims.

SaleHoo moved for leave to take immediate discovery, which the court granted. SaleHoo then served a subpoena on GoDaddy.com, the SaleHooSucks.com registrar, seeking to learn the registrant’s identity. GoDaddy gave notice of the subpoena to Mr. Doe, who moved to quash it.

Since Mr. Doe had notice of the subpoena and had an opportunity to be heard, the court found the controlling question was whether “SaleHoo alleged facially valid claims and produced prima facie evidence to support of the elements of these claims within its control?” The court answered the question in the negative.

“Here, the court finds that SaleHoo has not met its burden to make a prima facie showing with respect to likelihood of confusion. Doe plainly uses ‘SaleHoo’ in its domain name and throughout its website, but it is not evident how Doe’s use is confusing or whether it has caused actual confusion. The court is particularly mindful that the average Internet user is unlikely to believe that <www.salehoosucks.com> is either an official SaleHoo website or in any way sponsored or approved by SaleHoo.”

Therefore, the court granted Mr. Doe’s motion to quash the subpoena.

The case cite is SaleHoo Group, Ltd. v. ABC Company, __ F. Supp.2d __, 2010 WL 2773801, No. 10-0671 (W.D. Wash. July 12, 2010) (Robart, J.).

First Amendment Protects Grand Theft Auto Against Trademark Infringement

The First Amendment protects the makers of the Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas video game against claims of trademark infringement, the Ninth Circuit found Nov. 5.

In E.S.S. Entertainment 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc., the owner of the Play Pen strip club sued the video game maker that allegedly depicted the club and its trademark in its fictional version of Los Angeles called “Los Santos.” In the game version, the club is called the “Pig Pen” (depicted below).

The artists who developed the game took inspiration from photographs of the Play Pen but used photos of other East Los Angeles locations to design other aspects of the fictional “Pig Pen.”

In 2005, E.S.S. filed suit in the Central District of California for state and federal trade dress infringement and unfair competition. The heart of its complaint was that Rock Star used its logo and trade dress without authorization and created a likelihood of confusion among consumers as to whether E.S.S. endorsed or is associated with the game.

Rock Star moved for summary judgment, arguing in pertinent part that regardless of whether it infringed E.S.S.’ trademark rights, the First Amendment protects it against liability.

The district court granted the motion (in a 55-page opinion), and E.S.S. appealed.

Applying the “Barbie Girl” case of Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., 296 F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2002), which protected MCA’s right to publish a song with Mattel’s BARBIE trademark in its title, the Ninth Circuit affirmed.

The court noted that “ESS argues both that the incorporation of the Pig Pen into the Game has no artistic relevance and that it is explicitly misleading. It rests its argument on two observations: (1) the Game is not ‘about’ ESS’s Play Pen club the way that ‘Barbie Girl’ was ‘about’ the Barbie doll in MCA Records; and (2) also unlike the Barbie case, where the trademark and trade dress at issue was a cultural icon (Barbie), the Play Pen is not a cultural icon.”

The court acknowledged these factual differences but found they missed the point. “Under MCA Records and the cases that followed it, only the use of a trademark with ‘no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever’ does not merit First Amendment protection. In other words, the level of relevance merely must be above zero. It is true that the Game is not ‘about’ the Play Pen the way that Barbie Girl was about Barbie. But, given the low threshold the Game must surmount, that fact is hardly dispositive. It is also true that Play Pen has little cultural significance, but the same could be said about most of the individual establishments in East Los Angeles. Like most urban neighborhoods, its distinctiveness lies in its ‘look and feel,’ not in particular destinations as in a downtown or tourist district. And that neighborhood, with all that characterizes it, is relevant to Rockstar’s artistic goal, which is to develop a cartoon-style parody of East Lost Angeles. Possibly the only way, and certainly a reasonable way, to do that is to recreate a critical mass of businesses and buildings that constitute it. In this context, we conclude that to include a strip club that is similar in look and feel to the Play Pen does indeed have at least ‘some artistic relevance.’”

Commentary on the appeal from Eric Goldman here, and on the underlying district court decision from the Gamasutra here.

The case cite is E.S.S. Entertainment 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc., __ F.3d __, 2008 WL 4791705, No. 06-56237 (9th Cir. Nov. 5, 2008).