Entries in Functionality (5)

The Basics of "Look and Feel" and Personality Rights Under U.S. Law

I’m now back from Germany, where I traveled to help with a program sponsored by the University of Washington School of Law.

It combined UW law students with law students from Europe. The Europeans learned about American intellectual property law, and the Americans learned how they do things in Europe.

I spoke on two topics: “look and feel” protection under U.S. trademark law, and right of publicity under U.S. law. These issues come up from time to time in my practice, so they may be of interest to trademark owners.

The takeaway for “look and feel” protection: distinctive elements of product packaging, store interiors, or product design can be protectable under trademark law as “trade dress” if together they tell consumers where the product comes from. In other words, if they function the source-identifying role that trademarks play.

However, there are two big caveats. First, the elements can’t be functional. If they serve a useful purpose, they can’t be protectable under trademark law (though they could be protectable under patent law). Second, if they are part of the product themselves, the owner must prove that they have acquired secondary meaning, meaning that over time consumers have come to associate the trade dress (such as the product color, shape, or style) with a particular producer. Until that happens, product features can be freely copied.

The most important thing to know about right of publicity protection is that some states — including Washington — have statutes that protect against the commercial use of a person’s name, likeness, and voice without the person’s permission. The First Amendment is the biggest exception to such protection. The press can do most anything it likes without fear of liability. So can artists — as long as the artist embellishes the literal image of a person enough to transform it into a work of art (regardless of whether the art is good or bad, flattering or critical). Almost everyone else needs the person’s permission before making use of their “personality” in marketing a product.

My slides are available here (look and feel) and here (right of publicity).

Different Look Didn't Turn Functional Design into Protectable Trade Dress

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

It doesn’t happen terribly often.

In fact, I don’t think it happens nearly enough. Awarding the prevailing party attorney’s fees in a trademark case, that is.

But that’s what happened in Secalt S.A. v. Wuxi Shenxi Const. Mach. Co., Ltd., 668 F.3d 677 (9th Cir. 2012), where plaintiffs claimed trade dress protection in their industrial-strength traction hoist.

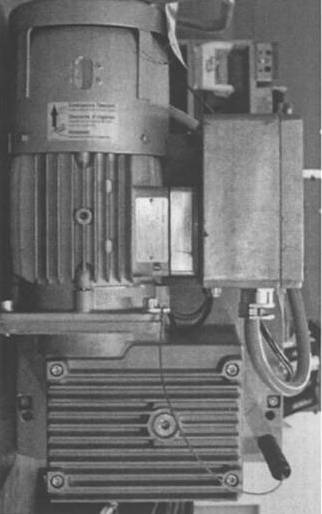

Plaintiffs Secalt, S.A., and Tractel, Inc. (“Tractel”), argued the overall exterior appearance of their hoist is nonfunctional because the hoist’s design—wherein the component parts meet each other at right angles—provide a distinctive “cubist” look and feel.

Tractel claimed its trade dress consisted of: “1) a cube-shaped gear box with horizontal fins; 2) a cylindrical motor mounted in an off-set position on the cube and partially overhanging the edge of the cube; 3) the cylindrical motor including vertical fins on a lower portion and a generally smooth sheet metal upper cover having a control descent lever and top cap positioned over the upper end and supported by rectangular legs; 4) a rectangular control box cantilevered to the motor by a square shaped member, the control box positioned over the cube, the control box including controls thereon; and 5) a rectangular frame.”

As evidence that these features aren’t functional, Tractel argued they were protected by a third party’s design patent.

The District of Nevada, however, didn’t buy the idea that the subject features weren’t functional. It granted summary judgment for the defendant and awarded attorney’s fees as an “exceptional” case.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit found Tractel didn’t seem to understand that functional features can’t be protected under trade dress law simply because they are different than what the competition offers.

It wrote: “Tractel’s fundamental misunderstanding—which infects its entire argument—is that the presumption of functionality can be overcome on the basis that its product is visually distinguishable from competing products. While such distinctive appearance is necessary, it is here insufficient to warrant trade dress protection.”

It found that “[e]xcept for conclusory, self-serving statements, Tractel provides no other evidence of fanciful design or arbitrariness; instead, here, ‘the whole is nothing other than the assemblage of functional parts, and where even the arrangement and combination of the parts is designed to result in superior performance, it is semantic trickery to say that there is still some sort of separate ‘overall appearance’ which is non-functional.’”

Interestingly, the court did not find that Tractel acted in bad faith. Yet, the lack of bad faith didn’t save Tractel from an award of attorney’s fees.

“Although Tractel does not ultimately prevail, were it able to provide some legitimate evidence of nonfunctionality, this case would likely fall on the unexceptional side of the dividing line. When summary judgment motions were heard, the parties had been in discovery for almost two years, taken multiple depositions, and compiled substantial documents. Yet, Tractel could not identify the aesthetic value of the exterior design, and was reduced to arguing that it was pursuing a ‘cubist’ look and feel even though its own witnesses undercut this argument.”

The court concluded that “Tractel’s action appears to be a conscious, albeit misguided, attempt to assert trade dress rights in a non-protectable machine configuration.” On that ground, it affirmed the district court’s judgment and upheld the award of attorney’s fees to the tune of $836,899.99. (The court also upheld the district court’s finding that the rates defense counsel charged — $320 to $685 per hour in 2010 — were “reasonable.”)

Las Vegas Trademark Attorney’s discussion of its home-grown case here.

Court Dismisses Glassybaby's Trade Dress Claims with Leave to Amend

Glassybaby’s (left) and a defendant’s votive candle holders

Glassybaby’s (left) and a defendant’s votive candle holders

Folks may remember that local candle holder designer Glassybaby, LLC, filed trade dress claims against competing designers in April (STL post here).

On June 6, Western District Judge Marsha Pechman dismissed those claims. In short, she found they weren’t adequately pleaded in plaintiff’s complaint.

The court wrote that “Defendants argue that the complaint fails to identify the mark or illustrate the so-called distinctive design. Plaintiff’s complaint states that the hand-blown glass containers are distinctive, but it does not describe the design in any detail. It is not possible to determine what the features of the votive candle holders are and whether they are functional or non-functional. This is not adequate to satisfy Rule 12(b)(6). Plaintiff must plead with at least some detail what the purported design is and how it is non-functional.”

The court similarly dismissed plaintiff’s dilution and Consumer Protection Act claims. However, it granted plaintiff leave to attempt to correct its pleading deficiencies in an amended complaint.

The case cite is Glassybaby, LLC v. Provide Gifts, Inc., No. 11-00380 (W.D. Wash. June 6, 2011) (Pechman, J.).

Robin's Egg Blue: For Tiffany, a Color Mark. For Others, a Fashionable Color

Tiffany’s iconic robin’s egg blue (top) — and Burberry’s new purse

Tiffany’s iconic robin’s egg blue (top) — and Burberry’s new purse

Robin’s egg blue. It’s all over Tiffany. Tiffany even has a registration for its blue box.

Yet, robin’s egg blue isn’t exclusively Tiffany’s. In fact, it appears to be one of this year’s hot colors. I’ve seen it on furniture at Roche Bobois and Macy’s. Last week I came across it again on a Burberry handbag at Nordstrom. (On my way to the men’s department, I swear.)

If robin’s egg blue were used by sellers of low-cost items, this might amount to trademark infringement or dilution. But when used by sellers of luxury items, it paradoxically appears to be ok.

Now, Roche Bobois, Macy’s, and Burberry aren’t using robin’s egg blue on boxes that contain jewelry. But they do sell items that involve jewelry, and Tiffany sells items that involve furniture and handbags. Nor are the colors exactly the same, but they’re close — to my eye, closer than the photos here indicate.

It’s interesting that a color that has become so iconic, so intertwined with the goodwill of one luxury retailer is being used with increasing frequency by other luxury retailers. I’m not saying that Tiffany isn’t enforcing its rights, or the other sellers are trying to pass off their goods as coming from Tiffany. Indeed, Roche Bobois, Macy’s, and Burberry have terrific reputations of their own. I suppose what I’m noticing is simply the intersection between trademarks (where one company uses the color to identify the source of its goods) and aesthetic functionality (where other companies use the color because it’s in fashion).

Seattle Law Professor Takes on AT&T and the PTO's Registration of Signal Bar Design

UW School of Law Professor Sean O’Connor, guest blogging at Legal Satyricon, writes about AT&T’s trademark registration of the bars indicating cell phone signal strength (depicted left).

UW School of Law Professor Sean O’Connor, guest blogging at Legal Satyricon, writes about AT&T’s trademark registration of the bars indicating cell phone signal strength (depicted left).

“The bars are purely functional representations of the strength of cell service and a standardized one at that,” he writes. “If anything were unworthy of being captured as a trademark, this should have been it.

To his dismay, AT&T’s bold use of “SM” to indicate its claim to common law rights in the design last year was replaced with an even bolder ”®” to indicate its federal registration, albeit on the Supplemental Register.

“While I am aghast at the chutzpah of the attorneys who sought to register a blatantly functional, generic icon as a proprietary trademark, I reserve my highest scorn for the PTO.”

A spirited discussion follows the post. Nice debut, Sean!