Entries in False Designation of Origin (41)

Similar Facts, Different Results: Ninth Circuit Decides Sports Likeness Cases

Celebrities’ right of publicity claims are stronger than their Lanham Act claims, the Ninth Circuit recently found. At least in some situations.

On July 31, the court decided two cases former football players brought against Electronic Arts, Inc. The players argued the video game publisher featured avatars that many users would recognize as depicting them, without their permission.

In one case, former college quarterback Samuel Keller, representing similarly-situated former college football and basketball players, argued the use violated his right of publicity under California state law — the statutory right to stop the unauthorized use of his likeness for commercial purposes. In the other, former pro football great Jim Brown focused on the federal Lanham Act, arguing that use of avatars with his likeness was likely to confuse consumers into believing the players had endorsed EA’s games.

In the Keller case, EA filed a motion to strike under California’s statute against Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, arguing its use of Keller’s likeness was protected by the First Amendment. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s finding that EA’s use was not constitutionally protected as a matter of law. It instead applied the “transformative use” test the court had applied in earlier right of publicity cases, finding that EA’s use of Keller’s likeness was the reason why consumers would purchase its games — not because its artistic expression had transformed his likeness into something akin to an expressive work of art.

The court concluded: “Under the ‘transformative use’ test developed by the California Supreme Court, EA’s use does not qualify for First Amendment protection as a matter of law because it literally recreates Keller in the very setting in which he has achieved renown.”

In the Brown case, similar facts yielded the opposite result. Due to a different claim for federal jurisdiction. Brown relied on the Lanham Act rather than a state claim for right of publicity.

That difference made all the difference. As a Lanham Act claim, the court applied prior precedent adopting what’s known as the “Rogers” test. Under that test, Lanham Act claims “will not be applied to expressive works ‘unless the [use of the trademark or other identifying material] has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless the [use of trademark or other identifying material] explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.’”

Applying that test, the court affirmed the district court’s dismissal of Brown’s claim.

“As expressive works, [EA’s] Madden NFL video games are entitled to the same First Amendment protection as great literature, plays, or books. Brown’s Lanham Act claim is thus subject to the Rogers test, and we agree with the district court that Brown has failed to allege sufficient facts to make out a plausible claim that survives that test. Brown’s likeness is artistically relevant to the games and there are no alleged facts to support the claim that EA explicitly misled consumers as to Brown’s involvement with the games. The Rogers test tells us that, in this case, the public interest in free expression outweighs the public interest in avoiding consumer confusion.”

Big decisions, both. Among other things, they illustrate how legal strategy can determine how similar cases can yield opposite results.

The case cites are In re NCAA Student-Athlete Name & Likeness Licensing Litig., __ F.3d __, No. 10-15387, 2013 WL 3928293 (9th Cir. July 31, 2013), and Brown v. Elec. Arts, Inc., __ F.3d __, No. 09-56675, 2013 WL 3927736 (9th Cir. July 31, 2013).

Omission of "Made in China" Label Makes Manufacturer Liable

Here’s a local Lanham Act case with interesting facts. It’s about the sale of waterproof notebooks used by the U.S. military.

Defendant J.L. Darling, Corp. manufactures waterproof paper, which it used in notebooks it sold to the military through its distributor, plaintiff Ira Green, Inc. After Darling terminated the Green’s distributorship, Green found a new source of waterproof paper located in China and proceeded to compete with Darling by selling notebooks using the new paper. However, Green did not place any “made in China” labels on its notebooks until after a Customs and Border Patrol Agent ordered it to do so.

Among various patent, trademark, and false advertising claims the parties allege against each other, Darling claimed that Green’s omission of the “made in China” labels amounted to falsely marking the country of origin of its notebooks, thereby deceiving consumers. Green responded that the issue was moot because it corrected its omission and that Darling provided no evidence that customers were deceived or that Darling suffered any resulting injury.

The parties brought cross-motions for summary judgment on their claims and counterclaims, including on Darling’s two Lanham Act claims for false designation of origin.

On Oct. 9, Western District Judge Robert Bryan granted Darling’s motion and denied Green’s.

It found: “While there is an issue of fact over when and how many of Green’s notebook products eventually received the correct ‘made in China’ stickers, there is no issue of fact that Green did not place the proper country of origin on its notebook products when it first distributed those products. Because the lack of sticker placement was a literally false omission, causation and damages are presumed unless Green can rebut this presumption. Green has shown no facts to rebut. Because Darling and Green both request summary judgment on these two claims, summary judgment should be granted and judgment of liability only entered for Darling, and summary judgment should be denied for Green, on Darling’s second and third Lanham Act claims (Counts II and III).

The case cite is Ira Green, Inc. v. J.L. Darling, Corp., No. 11-05796, 2012 WL 4793005 (W.D. Wash. Oct. 9, 2012) (Bryan, J.).

That's Not Fair! What Your Competitor Can't Do in Competing with You

Yesterday’s post was about false advertising, which got me thinking…. What are things a competitor can’t do in competing with you to make a sale?

Here’s a quick rundown:

- It can’t create a likelihood of confusion with you, if you came first. This is the essence of trademark infringement. A later-adopter can’t come into your market with a name or brand that is likely, i.e., probable, to confuse consumers into thinking that its goods or services come from you, are approved by you, or are affiliated with you. It doesn’t matter if your trademark is registered, since trademark rights automatically arise from use. It doesn’t even matter if your competitor was innocent in creating the likelihood of confusion. If its brand, company name, product name, or other marketing tool tends to mislead customers into thinking your competitor’s goods or services come from you, you may be able to put a stop to it. Caveats exist, but this is where the inquiry starts.

- It can’t misrepresent its product or your product. The right to free speech isn’t unlimited. Just like you can’t yell “fire” in a crowded theater, your competitor can’t lie about the qualities of its product or make a false comparison to your products. That means Honda can say Toyota’s cars are wimpy (in its humble opinion), but it can’t say its cars get twice the gas mileage Toyotas get when that’s not true (since it’s a statement of fact that’s provably false).

- It can’t use your trademark in its domain name. This is cybersquatting. It means no one — regardless of whether they’re a competitor — can register your trademark (or a confusingly similar variation) as part of its domain name in the hopes of either ransoming the domain name to you or profiting from Web traffic that was meant for your site. The Lanham Act provides for statutory damages that begin at $1,000 and go up to $100,000 per infringing domain name, as well as an award of attorney’s fees. Again, there are caveats, but the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act gives trademark owners a big stick to use against bad actors that hope to take wrongful advantage of your brand in their domain names.

- It can’t use your brand as a search engine keyword. Maybe. This is still up in the air. But the Central District of California last year slapped one law firm from buying its competitor’s trademark as a search engine keyword, finding its doing so constituted willful trademark infringement. The court doubled the trademark owner’s lost profits to $292k and awarded it attorney’s fees. See Binder v. Disability Group, Inc., 772 F. Supp. 2d 1172 (C.D. Cal. 2011). It’s still a gray area, but Binder might get traction. It’s certainly gotten some courts’ attention.

- Other things your competitor can’t do. If your brand is a household name, no one (competitor or not) can use it in a way that would tend to lessen the impact your brand has on consumers. That’s trademark dilution. If you manufacture goods, no one can put your trademark on goods that aren’t made by you. That’s counterfeiting. A competitor can’t say its goods — most commonly agricultural products — come from your special part of the world if they don’t. (This means a shellfish company can’t say its oysters come from pristine Penn Cove when they were grown in less favorable waters.) That’s a false designation of origin.

This list isn’t exhaustive, and there are a lot of gray areas. But hopefully this will help you put a label on your competitor’s bad acts when you know in your gut what they’re doing isn’t fair.

False Advertising Claim Over Surf Boards Rides Litigation Wave to Seattle

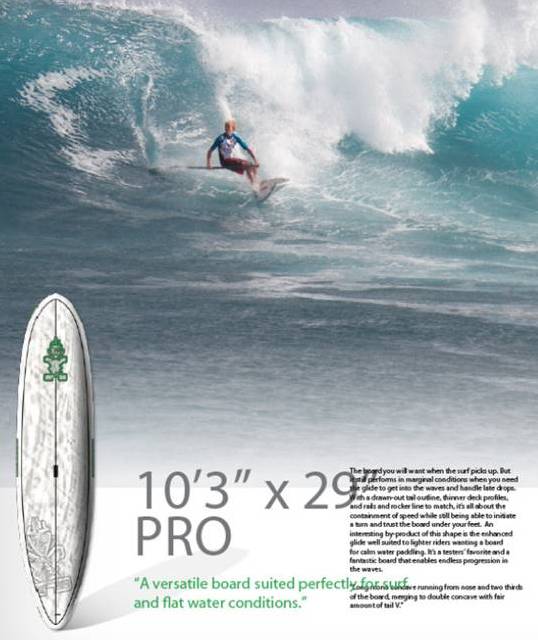

Whose board is it, anyway?

Whose board is it, anyway?

The catalog photo plaintiffs say defendants altered

A false advertising claim over competing stand-up paddle boards has ridden the litigation wave all the way to Seattle.

On March 9, plaintiffs Jimmy Lewis and Fuacata Sports LLC filed suit against competitors Trident Performance Sports Inc. and Starboard World Limited, alleging that defendants included a photo in their catalog showing one of plaintiffs’ custom, high-performance boards in competition — altered, so it appers to depict one of defendants’ production boards.

Plaintiffs’ complaint states that “[d]efendant Starboard World Limited created a 2011 Starboard SUP [Stand Up Paddleboard] product catalogue which incorporates a picture of a Starboard-sponsored athlete riding a Jimmy Lewis custom ‘gun’ board in extremely challenging Maui surf conditions. This photograph was placed on the same page as the Starboard Pro Wave ‘gun’ board, which was a new edition to the Starboard SUP product line. The photograph, found on page 52 of the 2011 Starboard SUP catalogue, was digitally altered to add Starboard Pro Wave pin [striping], carbon brush markings and a faint impression of the Starboard logo in order to lead consumers to believe the Jimmy Lewis custom board was the 2011 Starboard Pro Wave board. The depicted board was undeniably custom made by Jimmy Lewis and delivered as a blank board to the Starboard team rider.”

The complaint alleges that defendants used a similar photo in a national advertising campaign as well.

Plaintiffs allege defendants’ acts amount to “reverse passing off,” a legal theory in which the defendant “passes off” the plaintiff’s product as its own.

Defendants have not yet answered plaintiffs’ complaint.

The case cite is Jimmy Lewis v. Trident Performance Sports, Inc., No. 12-415 (W.D. Wash.).

Western District Finds Song Title Generic, Dismisses Trademark Claim

The song title “Mom Song” isn’t protectable as a trademark, Western District Judge Ricardo Martinez found last month.

He granted summary judgment in favor of comedian Anita Renfroe, who moved to dismiss comedian Frank Coble’s false designation of origin claim alleging that Ms. Renfroe’s “Momisms Song” about mothers infringed rights in his “Mom Song” about mothers.

The court found: “Mom Song’ is a generic mark that is not protectable. Indeed, virtually any song regarding the broad topic of motherhood could appropriately bear the same mark. The ‘Mom Song’ mark, which simply names the product to which it is attached, does not require ‘the exercise of some imagination … to associate [the] mark with the product,’ and, although the mark is descriptive in the most literal sense, the primary significance of the mark is to describe the type of product (i.e., a song about a mom) rather than its producer. Because the term ‘Mom Song’ ‘embrace[s] an entire class of products’ (i.e., songs about moms), it can receive no trademark protection. Allowing trademark protection for such a generic phrase would place an undue burden on competition, contrary to the goals of trademark law.”

The court also dismissed Mr. Coble’s claim for copyright infringement.

The case cite is Coble v. Renfroe, No. 11-0498, 2012 WL 503860 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 15, 2012) (Martinez, J.).