Entries from December 1, 2010 - December 31, 2010

"Eden Organic" Mark Owner Sues Over "Eatin' Organics"

Plaintiff’s and defendant’s logos

Plaintiff’s and defendant’s logos

Plaintiff Eden Foods, Inc., makes and sells organic foods.

Eden’s Organics, LLC, d/b/a Eatin’ Organics, LLC, delivers organic fruits and vegetables in Greater Seattle.

Eden Foods alleges that Eden’s Organics’ use of EDEN’S ORGANICS and EATIN’ ORGANICS infringes Eden Foods’ trademark registrations for EDEN, EDEN ORGANIC & DESIGN, and EDEN FOODS in connection with various vegetable products. It filed suit in the Western District on December 22.

Eden Foods’ complaint alleges a likelihood of confusion between the parties’ marks and uses and that a distributor has expressed actual confusion between the parties’ marks.

Eden’s Organics has not yet answered Eden Foods’ complaint.

The case cite is Eden Foods, Inc. v. Eden’s Organics, LLC, No. 10-2055 (W.D. Wash. Dec. 22, 2010).

"First-Class Mail" is a Protectable (and Registered) Trademark?

I ordered some photos online, which were delivered to me last week. The envelope was marked “USPS FIRST-CLASS MAIL.” That was expected, because I asked that the photos be sent by first-class mail. What wasn’t expected was the statement at the bottom of the mailing label that “FIRST-CLASS MAIL IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF THE UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE.”

Well, that’s true; I looked it up. In 1978, the U.S. Postal Service obtained a federal registration for FIRST-CLASS MAIL in connection with “delivery services — namely, delivery of letters and goods by mail,” with the word “mail” disclaimed as generic. (Interestingly, the claimed first-use date is July 1, 1863.)

But FIRST-CLASS MAIL is a protectable trademark?

It seems awfully generic to me. Not that I had much choice in the class of mail service I ordered, but if I had, I would have requested that the photos be delivered “first-class” because they presumably would be delivered faster than second class, third class, book rate, or whatever other classes of service that exist. I also would think that “first-class” delivery would be cheaper (though slower) than overnight delivery. In other words, by specifying delivery by “first-class mail,” I used the words that denoted the specified class of service I desired. A first-class job is a job that someone performs at the highest level. A first-class seat is a seat that comes with the best service. How could I communicate the service I wanted without using the words “first-class”? That would seem to make the mark generic.

Now, the U.S. Postal Service would say that FIRST-CLASS MAIL only means one thing — a particular service that you can get from the U.S. Postal Service. In other words, the mark isn’t generic because it identifies the source of the service. But for me, the portion of the mark that conveys that information is the portion the U.S. Postal Service disclaimed: “mail.” To my mind, Federal Express and United Parcel Service deliver letters and packages, but they don’t deliver “mail.” In any case, I don’t see why private delivery companies shouldn’t be able to denote a certain level of service as being “first class.” I suppose if it’s a descriptive mark, and the U.S. Postal Service has had its registration since the ’70s, it would be well-nigh incontestable, cutting off an attack on grounds of descriptiveness. But I still think “first-class mail” denotes the service rather than the provider of the service. And if not, it’s the disclaimed portion of the mark that conveys that distinction — the word the U.S. Postal Service says isn’t capable of doing so.

In the end, it seems silly to me that an online photo printer feels the need to clarify that by arranging to have the photos I ordered delivered in the manner I specified, it’s not infringing the U.S. Postal Service’s trademark.

Isn’t that obvious?

Western District Holds Cancellation is Not a Valid Independent Claim

In Basel Action Network v. International Association of Electronics Recyclers, both parties are non-profit organizations that certify businesses that recycle electronics products.

In June 2010, Basel sued IAER for a declaratory judgment that its use of the terms “certified electronics recycler” and “electronics recycler” does not infringe IAER’s CERTIFIED ELECTRONICS RECYCLER certification mark. Basel also sought to cancel the CERTIFIED ELECTRONICS RECYCLER registration on the ground that it is generic, among other grounds. (STL post on the complaint here.)

IAER moved to dismiss Basel’s claims.

On Dec. 13, Western District Judge Richard Jones found that Basel had not presented a justiciable controversy sufficient to sustain its declaratory judgment action.

The court then considered what appears to be a novel question in the Ninth Circuit: Can a plaintiff sustain an independent cause of action to cancel a defendant’s registration under Section 37 of the Lanham Act?

The court answered the question in the negative.

“The court holds that a party seeking cancellation of a registered mark must not only state an Article III controversy that cancellation can remedy, it must also state a valid independent cause of action that encompasses the controversy,” the court held. “The court reaches this conclusion for several reasons. First, Section 37 does not speak of a ‘controversy involving a registered mark,’ but rather an ‘action involving a registered mark.’ Second, if Congress had intended Section 37 to support a cause of action by itself, the court would expect the statute to explicitly provide for a cause of action. Third, no court has ever held that an Article III controversy that cannot stand as an independent claim can support a cancellation request.”

The court went on to find: “Every court to consider the issue has required a valid independent cause of action as a precondition for invoking Section 37’s cancellation remedy. The court in Universal Sewing Mach. Co. v. Std. Sewing Equip. Corp., 185 F. Supp. 257 (S.D.N.Y. 1960), reached the same conclusion as this court. The plaintiff there raised claims involving the registered mark, but none of them were cognizable in federal court. The court held that ‘absent some other basis of jurisdiction, a suit for cancellation by one in plaintiff’s position may not be independently maintained in this court.’ In Thomas & Betts Corp. v. Panduit Corp., 48 F. Supp. 2d 1088, 1093 (N.D. Ill. 1999), the court held that Section 37 does not by itself support a cause of action. It explained that the viability of the plaintiff’s cancellation claim depended on the viability of its separate Lanham Act unfair competition claim. If this court were to find a party could invoke Section 37 merely by articulating an Article III controversy, it would apparently be the first court to do so.”

The case cite is Basel Action Network v. International Association of Electronics Recyclers, No. 10-931 (W.D. Wash. Dec. 13, 2010) (Jones, J.).

The Gavel Drops: Results From the "Brand Name Auction"

The New York Times reported the “Brand Name Auction” raised a bunch of money — over $100k in all. (STL background post here.)

SHEARSON garnered the highest bid at $45,000, followed by MEISTER BRAU at $32,500 and HANDI-WRAP at $30,000.

I’m still not entirely sure what this money bought.

“You’re paying for a license for an interim period till the trademark issues,” NYT quoted one observer.

The Trademark Blog wonders if that means anything for marks that have never been used (after being abandoned) and the intent-to-use applications were signed when the applicants never had a bona fide intent to put the marks to actual use.

Right, the whole swearing-under-oath part of the application.

Notwithstanding that potential hitch, the auction apparently garnered public interest. The auction organizer told the World Trademark Review Blog his firm had 20,000 inquires from interested parties.

Apparently 45% of the inquiries came from private-label manufacturers; 45% came from entities that represent other brand manufacturers; and 10% from investors hoping to license the mark and from domain name owners seeking to marry their domain names with federal trademark registrations.

The organizer, a private investment firm, said the so-called first-ever trademark auction won’t be its last.

“We’ve made a decision to be in this space,” its CEO told the World Trademark Review a week before the auction was held. “Whatever happens at the auction will not deter us from owning this space.”

Abercrombie & Fitch Sues in Seattle for Cybersquatting and Unfair Competition

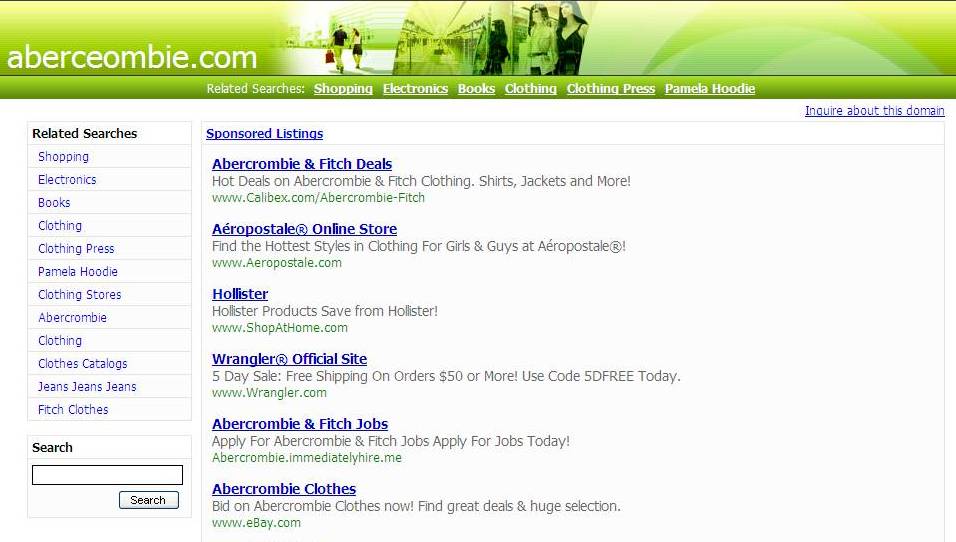

Screen shot from defendants’ Web site at www.aberceombie.com

Screen shot from defendants’ Web site at www.aberceombie.com

Subtlety isn’t their thing.

Abercrombie & Fitch Co. alleges that unknown defendants not only registered a truckload of domain names that are confusingly similar to its ABERCROMBIE and HOLLISTER registered trademarks, but those domain names resolve to Web sites that sell products that compete with Abercrombie & Fitch’s products, including products that allegedly are pirated from Abercrombie.

On December 10, Abercrombie filed suit in the Western District against John Does 1-10. Its complaint alleges cybersquatting, trademark infringement, and unfair competition.

Many of the domain names allegedly at issue include misspellings of ABERCROMBIE and HOLLISTER, such as aberceombie.com, abercromble.com, hollioster.com, and hiollister.com.

Abercrombie alleges the Western District has personal jurisdiction over the defendants because they have conducted business engaged in torts here.

Defendants have not yet appeared or answered the complaint.

The case cite is Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. John Does 1-13, No. 10-1998 (W.D. Wash.).