Entries in Lanham Act Section 43(a) (45)

That's Not Fair! What Your Competitor Can't Do in Competing with You

Yesterday’s post was about false advertising, which got me thinking…. What are things a competitor can’t do in competing with you to make a sale?

Here’s a quick rundown:

- It can’t create a likelihood of confusion with you, if you came first. This is the essence of trademark infringement. A later-adopter can’t come into your market with a name or brand that is likely, i.e., probable, to confuse consumers into thinking that its goods or services come from you, are approved by you, or are affiliated with you. It doesn’t matter if your trademark is registered, since trademark rights automatically arise from use. It doesn’t even matter if your competitor was innocent in creating the likelihood of confusion. If its brand, company name, product name, or other marketing tool tends to mislead customers into thinking your competitor’s goods or services come from you, you may be able to put a stop to it. Caveats exist, but this is where the inquiry starts.

- It can’t misrepresent its product or your product. The right to free speech isn’t unlimited. Just like you can’t yell “fire” in a crowded theater, your competitor can’t lie about the qualities of its product or make a false comparison to your products. That means Honda can say Toyota’s cars are wimpy (in its humble opinion), but it can’t say its cars get twice the gas mileage Toyotas get when that’s not true (since it’s a statement of fact that’s provably false).

- It can’t use your trademark in its domain name. This is cybersquatting. It means no one — regardless of whether they’re a competitor — can register your trademark (or a confusingly similar variation) as part of its domain name in the hopes of either ransoming the domain name to you or profiting from Web traffic that was meant for your site. The Lanham Act provides for statutory damages that begin at $1,000 and go up to $100,000 per infringing domain name, as well as an award of attorney’s fees. Again, there are caveats, but the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act gives trademark owners a big stick to use against bad actors that hope to take wrongful advantage of your brand in their domain names.

- It can’t use your brand as a search engine keyword. Maybe. This is still up in the air. But the Central District of California last year slapped one law firm from buying its competitor’s trademark as a search engine keyword, finding its doing so constituted willful trademark infringement. The court doubled the trademark owner’s lost profits to $292k and awarded it attorney’s fees. See Binder v. Disability Group, Inc., 772 F. Supp. 2d 1172 (C.D. Cal. 2011). It’s still a gray area, but Binder might get traction. It’s certainly gotten some courts’ attention.

- Other things your competitor can’t do. If your brand is a household name, no one (competitor or not) can use it in a way that would tend to lessen the impact your brand has on consumers. That’s trademark dilution. If you manufacture goods, no one can put your trademark on goods that aren’t made by you. That’s counterfeiting. A competitor can’t say its goods — most commonly agricultural products — come from your special part of the world if they don’t. (This means a shellfish company can’t say its oysters come from pristine Penn Cove when they were grown in less favorable waters.) That’s a false designation of origin.

This list isn’t exhaustive, and there are a lot of gray areas. But hopefully this will help you put a label on your competitor’s bad acts when you know in your gut what they’re doing isn’t fair.

Ninth Circuit Affirms False Advertising Finding Against Skydiving Marketer

Skydive Arizona, Inc., has sold skydiving services under its SKYDIVE ARIZONA trademark since 1986.

Cary Quattrocchi, Ben Butler, and others, d/b/a 1800SkyRide (“Skyride”), operate an advertising service that makes skydiving arrangements for customers and issues certificates that can be redeemed at a number of skydiving drop zones.

Skydive Arizona sued Skyride in the District of Arizona for false advertising, trademark infringement, and cybersquatting. On its false advertising claim, it alleged that Skyride misled consumers wanting to skydive in Arizona by stating that Skyride owned skydiving facilities in Arizona when it did not. It also alleged that Skyride deceived consumers into believing that Skydive Arizona would accept Skyride’s skydiving certificates when it would not.

Following partial summary judgment and a trial, a jury awarded Skydive Arizona $1 million in actual damages for false advertising, $2.5 million in actual damages for trademark infringement, $2,500,004 in profits resulting from the trademark infringement, and $600,000 for statutory cybersquatting damages.

Skyride appealed the court’s finding of liability for false advertising on summary judgment on the ground its false statements were not material to consumers’ purchasing decisions. In particular, Skyride argued that customer James Flynn’s declaration that supported the materiality element was ambiguous and fell short of survey evidence that courts often accept as proof.

The Ninth Circuit wasn’t convinced. “Skydive Arizona’s decision to proffer declaration testimony instead of consumer surveys to prove materiality does not undermine its motion for partial summary judgment. Although a consumer survey could also have proven materiality in this case, we decline to hold that it was the only way to prove materiality. Indeed, as we held in Southland Sod [Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1140 (9th Cir.1997)], consumer surveys tend to be most powerful when used in dealing with deceptive advertising that is ‘literally true but misleading.’ Here, Defendants’ advertisements were both misleading and false. Flynn’s declaration proved that consumers had been actually confused by SKYRIDE’s websites and advertising representations. The district court’s materiality finding was further supported by Skydive Arizona’s evidence of numerous consumers who telephoned or came to Skydive Arizona’s facility after having been deceived into believing there was an affiliation between Skydive Arizona and SKYRIDE.”

The case cite is Skydive Arizona, Inc. v. Quattrocchi, __ F.3d. __, No. 10-16196, 2012 WL 763545 (9th Cir. Mar. 12, 2012).

False Advertising Claim Over Surf Boards Rides Litigation Wave to Seattle

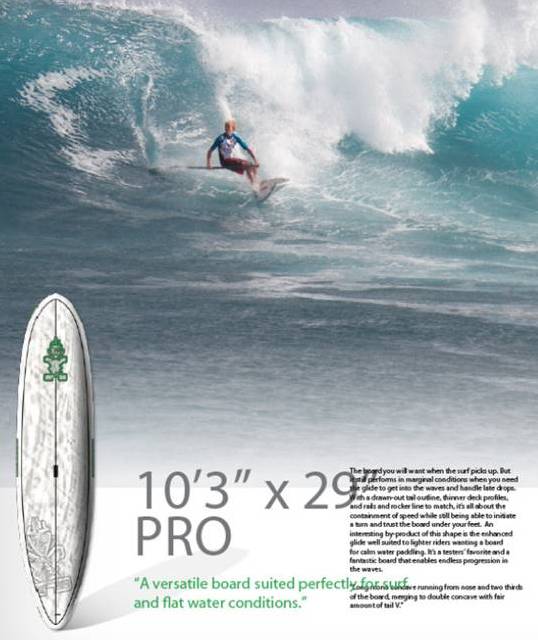

Whose board is it, anyway?

Whose board is it, anyway?

The catalog photo plaintiffs say defendants altered

A false advertising claim over competing stand-up paddle boards has ridden the litigation wave all the way to Seattle.

On March 9, plaintiffs Jimmy Lewis and Fuacata Sports LLC filed suit against competitors Trident Performance Sports Inc. and Starboard World Limited, alleging that defendants included a photo in their catalog showing one of plaintiffs’ custom, high-performance boards in competition — altered, so it appers to depict one of defendants’ production boards.

Plaintiffs’ complaint states that “[d]efendant Starboard World Limited created a 2011 Starboard SUP [Stand Up Paddleboard] product catalogue which incorporates a picture of a Starboard-sponsored athlete riding a Jimmy Lewis custom ‘gun’ board in extremely challenging Maui surf conditions. This photograph was placed on the same page as the Starboard Pro Wave ‘gun’ board, which was a new edition to the Starboard SUP product line. The photograph, found on page 52 of the 2011 Starboard SUP catalogue, was digitally altered to add Starboard Pro Wave pin [striping], carbon brush markings and a faint impression of the Starboard logo in order to lead consumers to believe the Jimmy Lewis custom board was the 2011 Starboard Pro Wave board. The depicted board was undeniably custom made by Jimmy Lewis and delivered as a blank board to the Starboard team rider.”

The complaint alleges that defendants used a similar photo in a national advertising campaign as well.

Plaintiffs allege defendants’ acts amount to “reverse passing off,” a legal theory in which the defendant “passes off” the plaintiff’s product as its own.

Defendants have not yet answered plaintiffs’ complaint.

The case cite is Jimmy Lewis v. Trident Performance Sports, Inc., No. 12-415 (W.D. Wash.).

Fishing Equipment Maker Says Advertised Breaking Weights False, Unfair

In fishing, the more weight equipment can hold makes a big difference.

Therefore, misstating the breaking point isn’t playing fair.

That’s what fishing equipment maker SPRO Corp. alleged in the false advertising complaint it filed in the Western District against competitors Eagle Claw Fishing Tackle Co. and Wright & McGill Co.

The complaint alleges that defendants represent that each of their fishing swivel products has a breaking strength that exceeds a particular weight (e.g., “The packaging of Defendants’ Size 2 swivel states that its breaking strength is 230 pounds”).

The complaint also alleges that SPRO sent defendants’ swivels to an independent laboratory for strength and failure analysis, which determined that defendants’ swivels break at weights below their advertised breaking strength.

Defendants have not yet answered SPRO’s complaint. SPRO filed its complaint in September, but it did not ask the court to issue summonses for defendants until until last week.

The case cite is SPRO Corp. v. Eagle Claw Fishing Tackle Co., No. 11-1507 (W.D. Wash.).

Western District Holds Trademark Infringement Defendant in Contempt

My foreign LL.M. students are sometimes skeptical that parties listen to the court when it orders them to do something, or to stop doing something. That’s apparently not always the case around the world. But here, fortunately, parties obey court orders — or suffer the consequences.

The consequences have not yet come to pass in T-Mobile USA, Inc. v. Terry. But they will.

In April 2010, T-Mobile filed suit in the Western District against Sherman Terry and a number of John Does, who T-Mobile claimed was selling unauthorized T-Mobile SIM cards and unlocked cell phones.

T-Mobile’s complaint specifically alleges that “Defendants are engaged in, and knowingly facilitate others to engage in, unlawful business practices involving the unauthorized and unlawful purchase and resale of T-Mobile Subscriber Identity Module (‘SIM’) cards and fraudulent activation of those SIM cards for use on T-Mobile’s FlexPay service, as well as the unauthorized and unlawful bulk purchase and resale of T-Mobile prepared wireless telephones, unauthorized and unlawful computer unlocking of T-Mobile Prepaid phones, alteration of proprietary software computer code installed in the Phones for T-Mobile, and trafficking of the Phones and SIM cards for profit.” T-Mobile alleges those acts amount to trademark infringement and false advertising, among other things.

In December 2010, the Court entered a preliminary injunction barring Mr. Terry and those acting in concert with him from purchasing, selling, altering, using, or shipping T-Mobile SIM cards, PIN numbers, activation codes, and other things needed to activate service or acquire airtime in connection with T-Mobile phones; purchasing, selling, unlocking, altering, advertising, or using T-Mobile prepaid handsets; and purchasing, selling, unlocking, altering, advertising, or shipping any device that bears T-Mobile’s trademarks, among other things.

Apparently, one of the defendants Mr. Terry didn’t heed the court’s order, because T-Mobile moved for an order of contempt.

On Oct. 21, the court granted T-Mobile’s motion. The court’s order — which states Mr. Collette Terry admitted he had violated the injunction — is recounted below.

“Following notice to the defendant, George Collette [presumably one of the John Doe defendants], a trial was scheduled for October 21, 2011 at 2:30 p.m. Plaintiff put on its first witness who testified about the actions of George Collette in violation of the Preliminary Injunction issued in this case. George Collette confessed that he violated the injunction. The Court, by clear and unequivocal evidence, finds George Collette guilty of civil contempt. The Court defers any sanction at this time. George Collette has assured this Court that he will not violate the injunction in the future. If subsequent acts by George Collette, [are] in violation of the injunction, the Court will address the issue of compensatory and coercive measures, to include the conduct which is the subject of this Order.”

There are a few lessons to be learned from this case, but I think they’re pretty obvious.

The case cite is T-Mobile USA, Inc. v. Terry, No. 11-5655 (W.D. Wash. Oct. 21, 2011) (Leighton, J.).