Entries in Trade Dress (53)

The Basics of "Look and Feel" and Personality Rights Under U.S. Law

I’m now back from Germany, where I traveled to help with a program sponsored by the University of Washington School of Law.

It combined UW law students with law students from Europe. The Europeans learned about American intellectual property law, and the Americans learned how they do things in Europe.

I spoke on two topics: “look and feel” protection under U.S. trademark law, and right of publicity under U.S. law. These issues come up from time to time in my practice, so they may be of interest to trademark owners.

The takeaway for “look and feel” protection: distinctive elements of product packaging, store interiors, or product design can be protectable under trademark law as “trade dress” if together they tell consumers where the product comes from. In other words, if they function the source-identifying role that trademarks play.

However, there are two big caveats. First, the elements can’t be functional. If they serve a useful purpose, they can’t be protectable under trademark law (though they could be protectable under patent law). Second, if they are part of the product themselves, the owner must prove that they have acquired secondary meaning, meaning that over time consumers have come to associate the trade dress (such as the product color, shape, or style) with a particular producer. Until that happens, product features can be freely copied.

The most important thing to know about right of publicity protection is that some states — including Washington — have statutes that protect against the commercial use of a person’s name, likeness, and voice without the person’s permission. The First Amendment is the biggest exception to such protection. The press can do most anything it likes without fear of liability. So can artists — as long as the artist embellishes the literal image of a person enough to transform it into a work of art (regardless of whether the art is good or bad, flattering or critical). Almost everyone else needs the person’s permission before making use of their “personality” in marketing a product.

My slides are available here (look and feel) and here (right of publicity).

Dripping Wax Seals Aren't Just for Bourbon Anymore

A dripping wax seal: Not just for bourbon anymore.

After Maker’s Mark’s solid trade dress victory this summer against Jose Cuervo — in which the Sixth Circuit upheld the district court’s finding the dripping red wax seal was an “extremely strong” trademark that had been infringed — it’s notable to see some dripping wax seals in the beer aisle. (I was there completely by accident, I assure you.)

Now, beer isn’t bourbon, and these seals aren’t red, but it will be interesting to see if Maker’s cries foul. I’m not saying it should, but on the heels of such a nice win, I wouldn’t be surprised if it tried to flex its muscle beyond hard liquor.

Ninth Circuit Reverses Functionality Finding for Skull-Shaped Vodka Bottle

Globefill’s trade dress: Not functional, the Ninth Circuit says

Globefill’s trade dress: Not functional, the Ninth Circuit says

Plaintiff Globefill Incorporated makes booze. So does defendant Elements Spirits, Inc.

In 2010, Globefill sued Elements in the Central District of California for trade dress infringement.

It described its trade dress in connection with its crystal head vodka as “a bottle in the shape of a human skull, including the skull itself, eye sockets, cheek bones, a jaw bone, a nose socket, and teeth, and including a pour spout on the top thereof.”

The Central District of California dismissed Globefill’s claim on grounds of functionality.

On May 23, the Ninth Circuit reversed, finding the skull design was purely ornamental.

“We typically consider four factors in determining whether a product feature is functional: ‘(1) whether the design yields a utilitarian advantage, (2) whether alternative designs are available, (3) whether advertising touts the utilitarian advantages of the design, (4) and whether the particular design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.’ Disc Golf Ass’n, Inc. v. Champion Discs, Inc., 158 F.3d 1002, 1006 (9th Cir. 1998).”

Applying these factors, the court found “the trade dress elements Globefill described in its operative complaint cannot be said to be functional as a matter of law. The skull design is ornamental and serves no utilitarian purpose; alternative bottle designs are available in abundance; and using the design increases, rather than decreases, Globefill’s manufacturing and shipping costs.”

Therefore, it found the trade dress was not functional and reversed.

The case cite is Globefill Inc. v. Elements Spirits, Inc., No. 10-56895, 2012 WL 1868861 (9th Cir. May 23, 2012).

Wiffle Ball Inc. Has Some Sweet Trade Dress!

Don’t blame the equipment:

Don’t blame the equipment:

Definitely not the reason I never made the pros.

Quick post just to revel in Wiffle Ball, Inc.’s sweet trade dress.

It’s been the same since I was a kid.

Yellow plastic bat, white plastic ball, red paper ball holder.

Just seeing it brings back a ton of good memories. Now that’s secondary meaning!

Different Look Didn't Turn Functional Design into Protectable Trade Dress

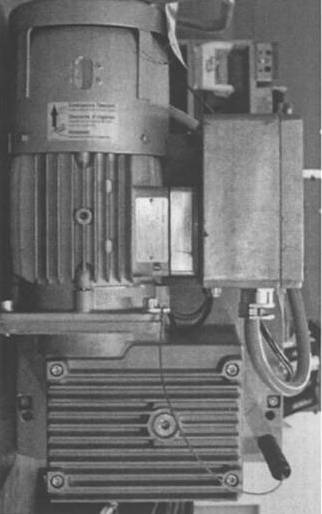

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

Protectable trade dress? Not even close, the Ninth Circuit finds

It doesn’t happen terribly often.

In fact, I don’t think it happens nearly enough. Awarding the prevailing party attorney’s fees in a trademark case, that is.

But that’s what happened in Secalt S.A. v. Wuxi Shenxi Const. Mach. Co., Ltd., 668 F.3d 677 (9th Cir. 2012), where plaintiffs claimed trade dress protection in their industrial-strength traction hoist.

Plaintiffs Secalt, S.A., and Tractel, Inc. (“Tractel”), argued the overall exterior appearance of their hoist is nonfunctional because the hoist’s design—wherein the component parts meet each other at right angles—provide a distinctive “cubist” look and feel.

Tractel claimed its trade dress consisted of: “1) a cube-shaped gear box with horizontal fins; 2) a cylindrical motor mounted in an off-set position on the cube and partially overhanging the edge of the cube; 3) the cylindrical motor including vertical fins on a lower portion and a generally smooth sheet metal upper cover having a control descent lever and top cap positioned over the upper end and supported by rectangular legs; 4) a rectangular control box cantilevered to the motor by a square shaped member, the control box positioned over the cube, the control box including controls thereon; and 5) a rectangular frame.”

As evidence that these features aren’t functional, Tractel argued they were protected by a third party’s design patent.

The District of Nevada, however, didn’t buy the idea that the subject features weren’t functional. It granted summary judgment for the defendant and awarded attorney’s fees as an “exceptional” case.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit found Tractel didn’t seem to understand that functional features can’t be protected under trade dress law simply because they are different than what the competition offers.

It wrote: “Tractel’s fundamental misunderstanding—which infects its entire argument—is that the presumption of functionality can be overcome on the basis that its product is visually distinguishable from competing products. While such distinctive appearance is necessary, it is here insufficient to warrant trade dress protection.”

It found that “[e]xcept for conclusory, self-serving statements, Tractel provides no other evidence of fanciful design or arbitrariness; instead, here, ‘the whole is nothing other than the assemblage of functional parts, and where even the arrangement and combination of the parts is designed to result in superior performance, it is semantic trickery to say that there is still some sort of separate ‘overall appearance’ which is non-functional.’”

Interestingly, the court did not find that Tractel acted in bad faith. Yet, the lack of bad faith didn’t save Tractel from an award of attorney’s fees.

“Although Tractel does not ultimately prevail, were it able to provide some legitimate evidence of nonfunctionality, this case would likely fall on the unexceptional side of the dividing line. When summary judgment motions were heard, the parties had been in discovery for almost two years, taken multiple depositions, and compiled substantial documents. Yet, Tractel could not identify the aesthetic value of the exterior design, and was reduced to arguing that it was pursuing a ‘cubist’ look and feel even though its own witnesses undercut this argument.”

The court concluded that “Tractel’s action appears to be a conscious, albeit misguided, attempt to assert trade dress rights in a non-protectable machine configuration.” On that ground, it affirmed the district court’s judgment and upheld the award of attorney’s fees to the tune of $836,899.99. (The court also upheld the district court’s finding that the rates defense counsel charged — $320 to $685 per hour in 2010 — were “reasonable.”)

Las Vegas Trademark Attorney’s discussion of its home-grown case here.