Entries from February 1, 2011 - February 28, 2011

If Parody is Exempt from Dilution, Why isn't It Exempt from Infringement?

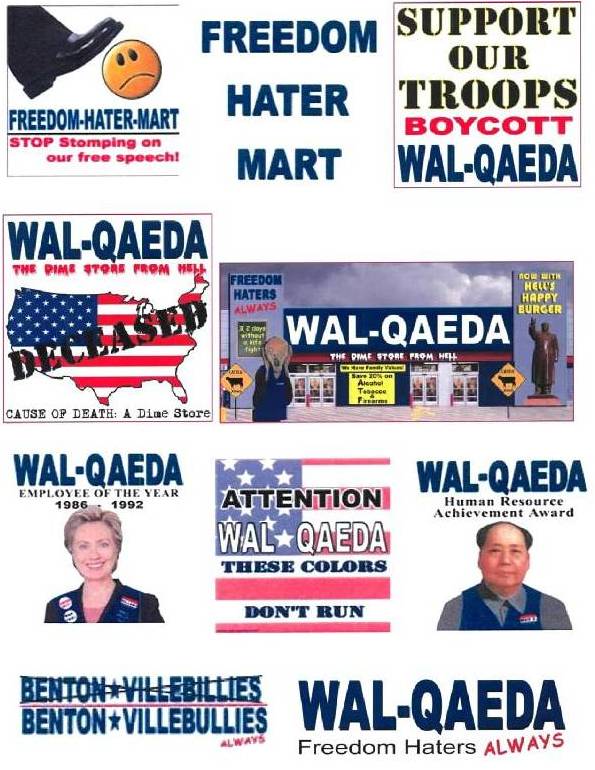

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Not commerical, so no dilution: Charles Smith’s WAL-QAEDA parody

Discussing parody in my Advanced Trademark Law Seminar.

I’m stumped on one point.

In a number of cases involving the parodic use of a trademark, courts apply likelihood of confusion analysis to infringement claims. Successful parodies do not cause a likelihood of confusion, so they do not infringe trademark rights.

Analyzing dilution claims, however, courts in the same cases often treat parodies as noncommercial speech. For that reason, they conclude parodic uses are exempt from dilution claims.

In Smith v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 537 F.Supp.2d 1302 (N.D. Ga. 2008), for example, the court concluded Charles Smith’s use of WAL-QAEDA was not likely to confuse consumers with Wal-Mart’s trademarks, so Wal-Mart’s infringement claim against him could not stand. With respect to Wal-Mart’s dilution claim, the court found WAL-QAEDA succeeded as a parody because it communicated Mr. Smith’s negative feelings about Wal-Mart. “Thus, Smith’s parodic work is considered noncommercial speech and therefore not subject to Wal-Mart’s trademark dilution claims….” In other words, Mr. Smith’s parody did not trigger the dilution statute because it was noncommercial.

Similarly, in MasterCard Intern. Inc. v. Nader 2000 Primary Committee, Inc., 2004 WL 434404, *9 (S.D.N.Y.), the court found Ralph Nader’s use of MasterCard’s trademarks in a political ad that spoofed MasterCard’s “Priceless” advertising campaign was not likely to confuse consumers, so it dismissed MasterCard’s infringement claim. With regard to its dilution claim, the court concluded the Nader campaign’s use of MasterCard’s mark was “political in nature, not within a commercial context, and is therefore exempted from coverage by the Federal Trademark Dilution Act.” Again, noncommercial use did not trigger the statute (though this time it was because the ad was political, not because it was a parody).

The answer’s probably sitting there in McCarthy on Trademarks, but if a use that’s deemed noncommercial does not trigger the dilution portion of the Lanham Act, why does it trigger the infringement portion of the Lanham Act?

I realize the dilution portion of the statute expressly excepts parodic and noncommercial use — and infringement finds its roots in common law —but if my use of a trademark is deemed to be noncommercial, why do I have to go through likelihood of confusion analysis to determine if such use nonetheless infringes a trademark owner’s rights? Seems like a finding that my use is noncommercial would be the same “Get Out of Jail Free” card for infringement that it is for dilution.

Anyone willing to tell me why it’s not?

Ninth Circuit Changes Dilution Standard

Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

Ninth Circuit: “Identical or nearly identical” doesn’t control.

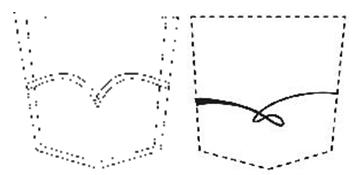

Levi’s and Abercrombie’s’ stitch designs

Interesting development in dilution in the Ninth Circuit.

Previously, Ninth Circuit courts required that a mark be “identical or nearly identical” to the plaintiff’s famous mark for dilution to exist.

That’s the standard the Northern District of California applied in Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Company, a dilution case over the parties’ stitching designs. (STL post on the district court’s 2009 decision here.) The court noted the advisory jury had not found that Abercrombie’s “Ruehl” design and Levi’s “Arcuate” mark were “identical or nearly identical,” a standard that required that “the two marks … be similar enough that a significant segment of the target group of customers sees the two marks as essentially the same.” The district court likewise found the marks did not meet that standard and entered judgment for Abercrombie.

Levi Strauss appealed. It argued that nothing in the dilution statute requires the defendant’s mark be “identical or nearly identical.”

Abercrombie responded by arguing the subject language arose out of Ninth Circuit case law that continued to exist even after the Trademark Dilution Revision Act replaced the earlier Federal Trademark Dilution Act.

The Ninth Circuit considered the origin of the “identical or nearly identical” language. It found that even though the language predated the FTDA, the circuit embraced the standard because it believed it was rooted in that iteration of the statute. The court then noted the TDRA replaced the FTDA in broad strokes. That led the court to question whether a legacy standard should continue to control. It concluded the legacy standard was replaced when the FTDA was replaced.

“Several aspects of the TDRA are worth noting. The first, as mentioned previously, is that Congress did not merely make surgical linguistic changes to the FTDA in response to Moseley [v. V. Secret Catalogue, Inc., 537 U.S. 418 (2003), which required a showing of “actual dilution”]. Instead, Congress created a new, more comprehensive federal dilution act. Furthermore, any reference to the standards commonly employed by the courts of appeals — ‘identical,’ ‘nearly identical,’ or ‘substantially similar’ — are absent from the statute. The TDRA defines ‘dilution by blurring’ as the ‘association arising from the similarity between a mark or a trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark.’ Moreover, in the non-exhaustive list of dilution factors that Congress set forth, the first is ‘[t]he degree of similarity between the mark or trade name and the famous mark.’ Thus, the text of the TDRA articulates a different standard for dilution from that which we utilized under the FTDA.”

The court found its departure from the “identical or nearly identical” standard was in line with the Second Circuit’s evaluation of Starbucks’ dilution claim based on use of the term CHARBUCKS for coffee in Starbucks Corp. v. Wolfe’s Borough Coffee, Inc., 588 F.3d 97 (2d Cir. 2009). In that case, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s finding that the dissimilarity between CHARBUCKS and STARBUCKS was “sufficient to defeat [Starbucks’] blurring claim.” It instead found: “The post-TDRA federal dilution statute … provides us with a compelling reason to discard the ‘substantially similar’ requirement for federal dilution actions. … Although ‘similarity’ is an integral element in the definition of ‘blurring,’ we find it significant that the federal dilution statute does not use the words ‘very’ or ‘substantial’ in connection with the similarity factor to be considered in examining a federal dilution claim.”

In summary, a new statute means a new standard — or at least no basis for the Ninth Circuit’s old standard to live on. Therefore, the court reversed the district court’s decision and remanded for further proceedings.

The case cite is Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Co., __ F.3d __, 2011 WL 383972, No. 09-16322 (9th Cir. Feb. 8, 2011).

Ninth Circuit Affirms Western District's Finding that "Vericheck" is Suggestive

A while back, the Western District in Lahoti v. Vericheck, Inc., found the VERICHECK trademark is suggestive when used in connection with check verification services. In doing so, it concluded that David Lahoti acted in bad faith when he registered the vericheck.com domain name.

In 2009, Mr. Lahoti appealed. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the bad faith finding. With regard to the classification of VERICHECK, it found: “[w]hile the district court perhaps could have relied exclusively on the registration of the Arizona Mark [also for VERICHECK for check verification services], it did not do so,” but instead “improperly required that the Mark describe all of [respondent] Vericheck’s services, examined the Mark in the abstract, and concluded that it could not analyze the Mark’s component parts.” Therefore, it vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded.

On remand, the Western District applied the Ninth Circuit’s direction in amended findings of fact and conclusions of law. It again concluded that VERICHECK is suggestive and, therefore, is entitled to protection as a trademark without a showing of secondary meaning.

Mr. Lahoti again appealed, arguing the district court again failed to analyze the VERICHECK mark in its industry context.

On Feb. 16, the Ninth Circuit affirmed. It found: “the district court indisputably recited the relevant legal principles that we set out. The district court then went on to find that, ‘[w]hen viewed in the context of Vericheck’s services, whether in whole or in part, including Vericheck’s check verification services, the VERICHECK mark does not immediately convey information about the nature of Vericheck’s services.’ The district court explained that, ‘in reaching [its] conclusion,’ it ‘considered the component parts of the VERICHECK mark ‘as a preliminary step on the way to an ultimate determination of the probable consumer reaction to the composite as a whole.” Thus, the district court conducted its analysis as instructed.”

STL background on the long-running case here, here, here and here.

The case cite is Lahoti v. Vericheck, Inc., __ F.3d. __, 2011 WL 540541, No. 10-35388 (9th Cir.) (Jan. 13, 2011).

Seattle eBay Seller's Lawsuit Against Coach Gets National Attention

Lots of media attention for Gina Kim’s class action lawsuit against Coach, Inc.

She says she used to work for Coach, had accumulated a few Coach handbags, and tried to sell them on eBay.

Ms. Kim says Coach accused her of selling counterfeit product and convinced eBay to pull her account. All without investigating whether her handbags were real or fake. So she sued for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement and for tortious interference with her relationship with eBay.

She now represents a class of persons she says have likewise been strong-armed by Coach.

AP story here; WSJ Law Blog post here.

It’s shameful if what Ms. Kim says is true. No matter how prevalent counterfeiting has gotten online, brand owners simply can’t assume all online sales of their goods are counterfeit. Accusing first and asking questions later just isn’t good policy. It’s against the law and suing innocent owners of the brand-owner’s product can’t be good for business.

Of course, Coach probably has a very different view of what allegedly happened.

We’ll see as the lawsuit unfolds — assuming it isn’t quickly settled.

PIE-brand Pie is the New CUPCAKE-brand Cupcake

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

Seattle pie maker Pie’s logo

And Seattle’s newest pie maker is Pie.

It stands to reason, then, that PIE-brand pie is the new CUPCAKE-brand cupcake.

Photo by STL